Solaqua: The Next Evolution in Solar – From Land to Sea

Solar cells are a favorite among renewable energies, especially in the more sunny countries further south. A remaining problem, however, is the available space: Solar cells produce less energy per square meter than conventional power plants. Hence, much larger areas are needed. This introduces a serious problem: The regions with the most significant energy needs are mostly highly populated. Thus, space is scarce. But what if we could install them in more unconventional locations – like at sea?

This question was tackled and answered by the Maltese startup Solaqua, which developed floating units of solar cells, placing them just off the shore. In today’s interview, we are talking to Professor Luciano Mule’Stagno, Co-founder of Solaqua and Director of the Institute of Sustainable Energy of the University of Malta.

How did You Start What You are Doing?

I am at the Institute of Sustainable Energy and have been their director for about six years. To begin with, I did my doctorate in Physics in materials science in the US, and I worked on Silicon – specifically silicon defects and their impact on semiconductor devices. After my PhD, I worked in Industry for 12 years, and when I came back to Malta, I was CEO of Heritage Malta for three years. In 2009/2010, I joined the University of Malta, and since then, I have been mostly working on solar energy – primarily on materials such as Silicon and on developing offshore solar systems. In the heritage part, I am still involved with the National Trust of Malta, an NGO.

What is the Institute About?

My area is primarily solar systems and materials, both experimentally and theoretically. Other people in the Institute do wind, offshore energy storage, energy in buildings, energy policy, and even legal aspects of energy. We are a small institute, but in the last ten years, it ramped up quite a bit. In the institute, we have about 15 people on the research staff, including 4 full-time academics, and 18 associate academics, people from other departments who work with us. We are part of the University of Malta, so any academic at the University can also be associated with us. We do engineering projects: for example, we collaborate with the the Mechanical and Electrical Engineering departments, but we also have a couple of candidates who want to dive into energy policy. We are getting quite a bit of interest in the last few years – from North Africa or Africa in general, where we also have some students now.

What is Solaqua About?

Solaqua is about offshore solar. We have been working on it for 11 years, and it is advanced. Floating solar has developed quite a bit in recent years, but it’s mostly on lakes and reservoirs – we are working on solar on the sea, which in our specific case is the Mediterranean Sea. We have developed a design and a website and are in the process of starting a startup right now. If all goes well, in 2024, we will launch the startup, and in 2025, we will launch the pilot.

How is Your System Designed?

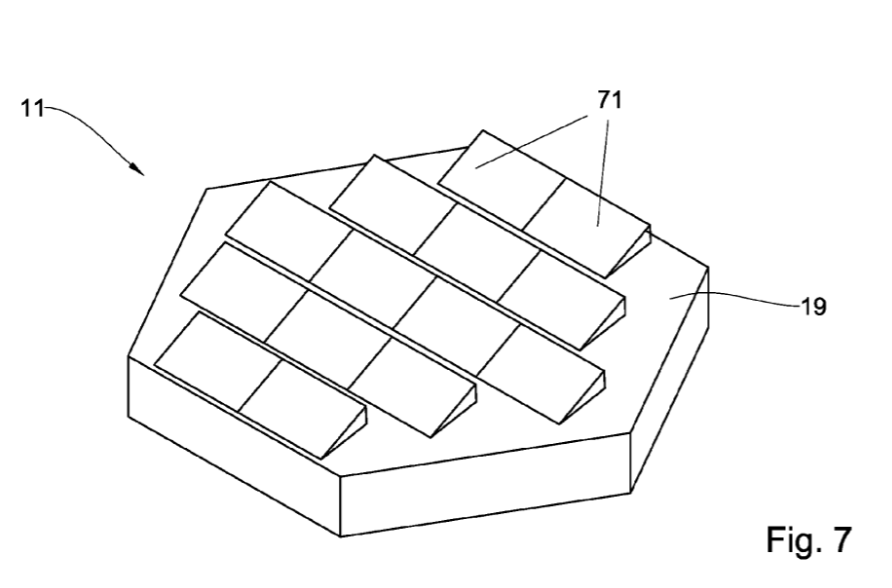

Our design uses a hexagonal platform of light concrete, which is 8 m in diameter and could accommodate about 14 solar panels installed on top of it. The concrete forms a shell 2 meters high, with the solar cells about 1 meter above sea level. We chose this design to keep costs down. Our system is modular and relatively small – so you can build it on land and launch it in the sea – and it is also relatively easy to make.

Some of the other people working on offshore units tend to build large metal structures, which are very robust but also very expensive, whereas we are trying to keep the costs down. Our targets are places like Malta or big cities near the sea, where land tends to be expensive – even for solar farms. Our units would be compatible even with land-based systems.

To this day, some people envision systems in which their solar panels are almost directly floating on the sea. The problems with these systems begin once you start thinking about practicality: Yes, panels are waterproof and made to get wet. But first, if they are constantly wet, I wonder if they will survive for 25 years. Secondly, if an area is continuously in contact with water, you might get biological growth – in our case, that happens only on the concrete shell. However, if your solar cells are constantly in contact with the water, biological growth might be directly on the glass.

Our solar cells are only getting wet in case of a storm, which you may envision once or twice a year in the Mediterranean. Also, the storm won’t harm them: The center of gravity is low, so they are safe. We simulated in the wave tank, testing up to 6-meter high waves. The prototype partially flows with the waves – some water will get on top, but not so much. The system is fine.

In the first project, we had several prototypes where we saw that if the waves were getting directly on the panels, they might actually break them: Panels are not so strong when you exert a force on the glass. However, since our current platform is partially moving with the waves, this problem is solved. We have a patent for our design.

We plan to put the systems in 50+ meters deep water – essentially very close to the shore, unlike wind energy, where you must go kilometers away. The sea tends to fall steeply in the Mediterranean – so 50 m in depth can be 50 to 100 m away from the coastline. The 50 m mark is because the flora and fauna in the water are much less populated at this depth, which means there are much fewer environmental concerns. If you go in shallow water, then in the Mediterranean area, you have Posidonia oceanica, a protected species, and you would not be able to install it there.

With our successful wave tank testing, we have proof of concept. The next step is to launch a startup with the funds to launch a pilot made of a few hexagonal basic units. If you want to attract the big guys who want to invest millions, it is better to have a pilot running.

How Did You Manage to Increase Your Output Even Further?

We have another patented mechanism for a cooling system for the panels, which gets us 10 to 15% more output. Now, the problem is, if you are running a pump at a constant rate, then you constantly lose a part of your energy. On the contrary, if you keep the water in a frame around the solar cells but never pump it up, there is still a cooling effect initially, and you still gain about 3% of increased efficiency.

In our system, we turn on the pump when needed. Once the water reaches 40°C, we exchange it all using the pump. This leads to an increase in efficiency of 10 to 15%. Using this “boost “to our efficiency, we can directly compete with land-based systems as we maximize our solar cells’ output.

In 2015, we tested a prototype without a cooling mechanism and found an output of about 3% more than that of a land-based system. The first reason is the cooling effect of the sea. But the second, for us at first surprising reason, was that the sea is much cleaner, so there is less dust than on land. This is an additional point for the offshore approach.

What are the Biggest Challenges You Faced?

The biggest challenge is not the design but the research system: If you were working for a company dedicated to such a project, you say, “We need this amount of money to make it work”, and the money comes. When you work as a researcher, on the other hand, you have to get funds and find new people every time. The research system can be challenging, but we navigated it – fairly successfully, as I would say.

And, of course, it is an unfinished project, so we have yet to say that we finally succeeded. But we are optimistic: We have already found a few companies interested in us. There is an Indian company interested in building it, and two or three years ago, we also spoke to Bahrain because, in the Gulf of Bahrain, there are conditions similar to those in the Mediterranean. So, I don’t think selling it will be difficult as soon as the pilot is running.

Whom to Contact?

Are you feeling inspired by this exciting idea and eager to explore more? Reach out to Luciano for a delightful discussion, or simply visit Solaqua to learn more about their work.