DVGW – Setting the Rules for Hydrogen

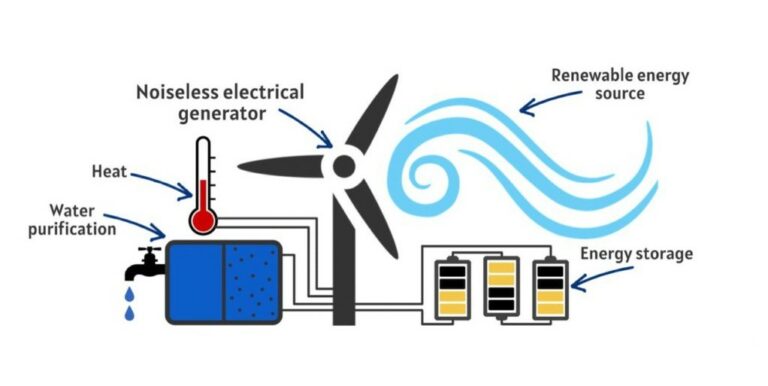

“Going green” – or changing existing technologies towards more sustainable ones – consists of complex transitioning steps. This transition encompasses changes to more intermittent forms of energy like wind or solar, more sustainable techniques for creating heat and replacing natural gas with hydrogen.

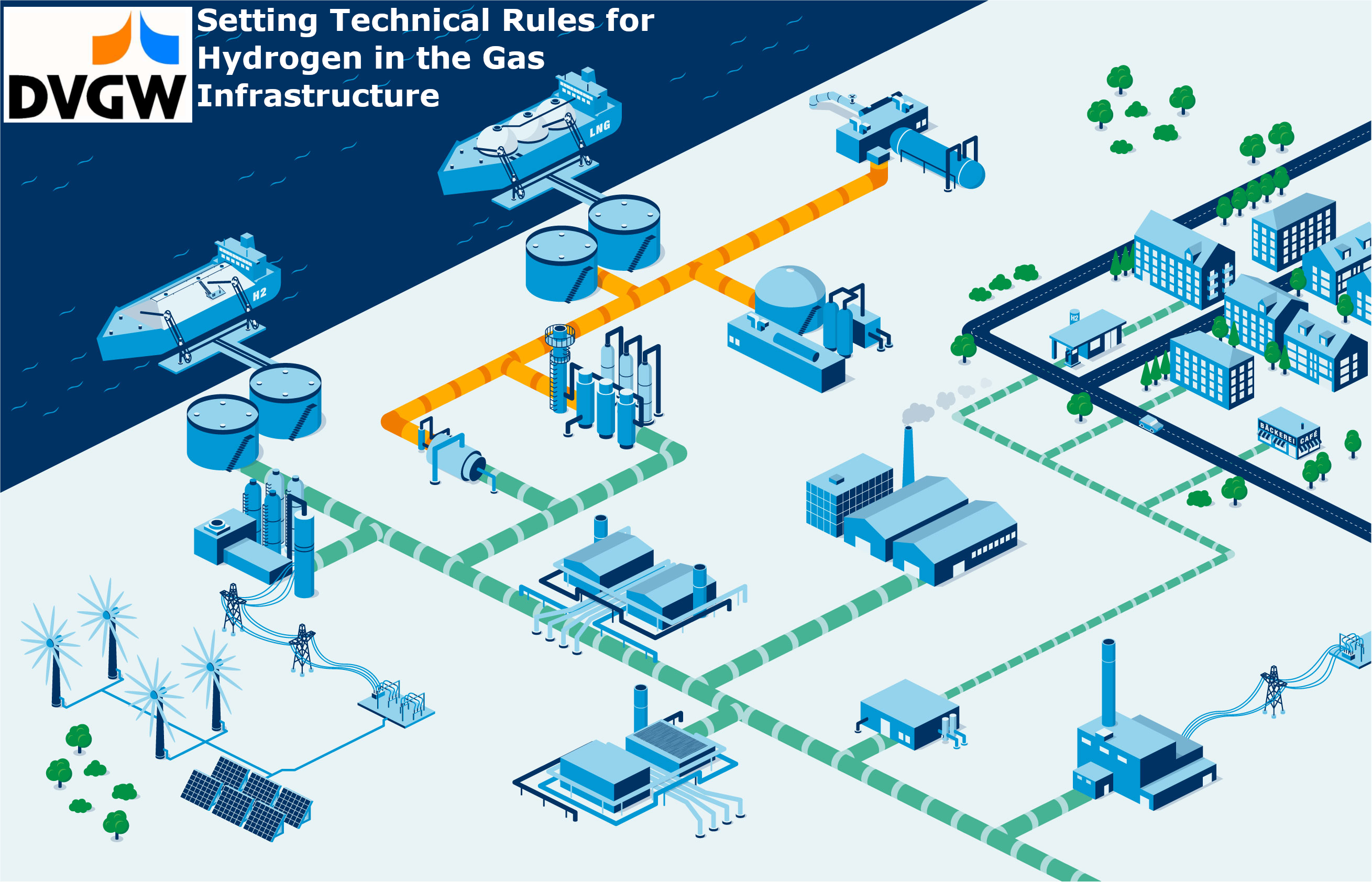

Hydrogen is a versatile gas that has the potential to act as transportation fuel, replace natural gas in power plants, or act as feedstock in chemical processes. Its new role was manifested in the European Union hydrogen strategy, passed in 2020, and is part of the European Green Deal.

However, it is not enough to “simply” start producing and using hydrogen immediately. Any new technology has risks that need to be minimized by proper handling. The appropriate handling of technology is encoded in guidelines and technical rules. The technical rules on how to deal with energy gases are set in Germany by the DVGW (Deutscher Verein des Gas- und Wasserfaches; German Technical and Scientific Association for Gas and Water). While natural gas usage has been known for a long time, old rules need to be adopted, and new ones need to be developed for the use of hydrogen.

In today’s interview, we talk with Michael Walter, the manager of the DVGW‘s innovation programme hydrogen, which delivers the technical and scientific facts for creating these rules.

What is DVGW?

DVGW is a technical-scientific association founded in 1859 in Frankfurt am Main, which makes it the oldest technical and scientific association in the world. Our work is divided into four pillars:

1. Technical rules

… that is also the reason for its founding. We set the technical rules with representatives from the industry for the gas industry, i.e., natural gas, methane, and hydrogen. We are also mentioned in paragraph 49 of the German Energy Industry Act (German: Gesetz über die Elektrizitäts- und Gasversorgung Energiewirtschaftsgesetz – EnWG). It says: “Anyone who wants to build a pipeline-based gas industry should do so by the rules of the DVGW.” Since 2021, the EnWG also explicitly names DVGW as institution for hydrogen infrastructures. The equivalent association on the electricity side mentioned in the EnWG is the Association of German Electrical Engineers (VDE; German: Verein Deutscher Elektroingenieure). In addition to gas and hydrogen, we are also responsible for drinking water: together with the honorary office from the industry, we set the rules for the drinking water infrastructure, for example, for the hygiene of the drinking water. Clean tap water in Germany is subject to the DVGW regulations.

2. Research and Development

That’s where I’m based. Why are we doing this? Technical rules are also based on technical and scientific findings. It’s about operational reasons but also about answering the question: What should be included in the regulations in the future and how can we safeguard the security of supply of gaseous energy?

3. Vocational training

The DVGW offers Meister courses – masterclasses, other training opportunities for water and gas industry specialists, network engineering, and certificate courses. The knowledge imparted in these courses is based on knowledge of the technical rules, e.g. on gas installation. Other topics covered come from the area of research and development, for example, new options for drinking water treatment or the topic of hydrogen.

4. Products and Services

One of our primary services is the certification of technical products, such as drinking water systems or gas appliances. DVGW CERT GmbH, a 100% subsidiary of DVGW, carries out the certification which is based on technical rules and is preceded by research and development.

Who are we doing this for?

On the one hand, the German Energy Industry Act stipulates two associations (the VDE and us – the DVGW) that set the technical rules, which then apply in Germany and, in some cases, throughout Europe or even worldwide, as we contribute to the ISO standards. Many companies outside of Germany use our rules to receive a certificate for their products in Germany. Other certifiers in Europe work similarly to us.

Of course, every certificate is also a quality feature. Let’s assume you go to the installer and see a boiler there and find a DVGW CERT test seal—and then you are more likely to buy this device than a device that does not have this seal. If a device does not have a seal at all, it may not comply with the applicable standards.

On the other hand….?

Research and Development at DVGW

…is located in our Technology and Innovation Management department and has two strands: An energy strand (hydrogen) and a water research strand. Today, we are talking about hydrogen. This line is called the energy line because it involves natural gas and other energy gases as well. The DVGW has had active research projects in the field of hydrogen since 2010, and we have been working more intensively on hydrogen since 2018.

The origins of the DVGW lie in town gas, a mixture of hydrogen and carbon monoxide. In the middle of the 19th century there were several questions around this gas type. To give the right answers and to exchange knowledge six persons gathered around with the idea to built an association for the gas industry. The general managers of roughly 50 gas utilities considered this as an excellent idea. And thus, the “Association of German Gas Expert and Authorized Representatives of German Gas Utilities” was founded on 21st of May 1859. Until the late 1960s, town gas was the main energy gas in the Federal Republic and the GDR. Then, due to treaties with the Soviet Union, the increased delivery of Dutch natural gas and safety concerns, as town gas contains carbon monoxide, a transition to the methane-based energy carrier took place. “Safe” is in quotation marks because every gas, especially combustible gasses must be handled with a sense of proportion and caution – if you handle a gas within the scope of the technical regulations, everything is safe. The conversion from town gas to natural gas in the Federal Republic essentially took place until the end of the 1970s; in the GDR, town gas was partly used until 1989 – after which the last pipes were converted to natural gas.

A switch from L-gas to H-gas also took place within natural gas operations: the gas used initially from the Netherlands came from North Sea reserves and had a relatively high nitrogen content (hence called low-calorific gas) – this is not the case for Russian high-calorific gas. The switch to Russian gas came as the Netherlands’ gas fields were slowly running out.

Hydrogen Research and Development

Today, another change is taking place: hydrogen. Our natural gas networks are slowly but surely converted into hydrogen or methane-based networks. Here, DVGW is the association who defines the technical rules for this transformation. Specifically, it is a reverse transformation since the previous town gas already contained hydrogen. The questions that need to be answered about the switch to hydrogen come, on the one hand, from the current operation of the gas infrastructure, but also arise from potential new technologies: Will there be hydrogen everywhere, or are there hydrogen islands? Will there be methane islands? And how does the whole thing fit into the European energy environment?

The Innovation Programme Hydrogen was submitted to the DVGW Executive Board in 2020, of which I am the manager and addresses, among others, the following questions:

- Are the steels used in the gas infrastructure suitable for hydrogen?

- The gas network uses steel and other materials, such as polyethylene pipes. What about these?

- What about the house connections?

- How do the devices connected to the grid behave when you switch to hydrogen or hydrogen-methane mixtures?

- How do valves, intermediate compressor stations, transfer stations from the transport to the distribution network, etc., behave?

- What do we have to consider regarding gas qualities?

- Do we have enough hydrogen available, and where does it come from?

The program has been running since 2021, and we have already been able to answer many questions – a second round of the innovation program will start soon.

An example we have already been able to answer is the suitability of the steel used, which an independent institute examined for us. The result is that all steel materials used in the gas network in Germany are hydrogen-compatible, when the grid transporting hydrogen is operated according the defined operating conditions of the gas network (see technical rules). Over 207 different materials and their geometries were investigated. The steel types used and examined date back to the 1930s. With the old tubes, the specific question arose about what would happen in the event of minor damage, such as a surface scratch. The results are very encouraging: Fracture mechanics investigations on pipes have shown that a pipe with a crack can be operated for at least 100 years until it breaks – provided that it is operated under the usual operating conditions given by the DVGW technical regulations. Factually, gas grid operators have to check the grid in an annual or even shorter interval, according the DVGW technical rules G 466-1 and G 465-1, respectively. Thus, a leak risk is minimized.

What about the existing fittings? These are also suitable for hydrogen.

What about lubricants and auxiliary materials? The current investigations are ongoing, but the preliminary results look promising.

In our new product, the verifHy database, manufacturers can enter their products and have their hydrogen suitability certified by the DVGW. Network operators can look into the database and find system and network components that are 100% hydrogen-compatible so that these certified products can replace devices that need to be replaced. What does this mean for a mix? A component with a 30% hydrogen mixture can also be used for a 100% proportion. And vice versa: Smaller proportions also work if 100% is not a problem.

The Innovation Programme Hydrogen comprises presently of 35 individual projects. During the course of the Innovation Programme Hydrogen additional questions arose that will be answered in a successor programme, including hydrogen derivates such as such as ammonia being a major topic in political discussions.

Whom to Contact?

Are you feeling inspired by this exciting idea and eager to explore more? Reach out to Michael for a delightful discussion, or simply visit their website to learn more.